Written by Amy Hufnagel and Giovanna Platina Phipps

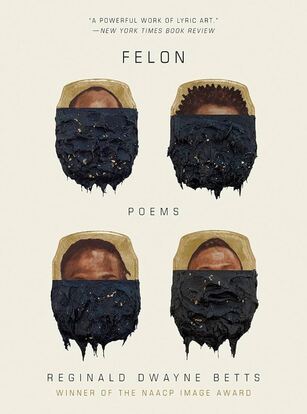

In honor of National Poetry Month, the SSPM highlights Reginald Dwayne Betts, a formerly incarcerated individual who is now an award-winning poet and lawyer. Additionally, he is the founder and Executive Director of Freedom Reads, an exceptional non-profit transforming access to literature within prisons by installing Freedom Libraries in facility housing blocks. The books chosen in these libraries are narratives of transformation, and also aid and confront the effect of imprisonment on the psyche/spirit. In addition to working tirelessly to get good books into the hands of incarcerated individuals, Betts is the author of a memoir and three collections of poetry. He recently transformed his latest collection of poetry, Felon, into a solo theater show that explores the post incarceration experience and lingering consequences of a criminal record

through poetry and personal stories.

In 2019, Betts won the National Magazine Award in the Essays and Criticism category for his NY Times Magazine essay that chronicles his journey from prison to becoming a licensed attorney, awarded a Radcliffe Fellowship from Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Emerson Fellow at New America, and most recently a Civil Society Fellow at Aspen. Betts holds a J.D. from Yale Law School. In Betts’ interview with Michal Martin, for Amanpour and Company, a PBS program and organization under PBS, he speaks about the impact of incarceration on identity, the power of written word, and the importance of forgiveness (full interview in YouTube link provided below). “I didn’t believe that my life was more valuable than the risks I was taking” said Betts as a 16 years old – sentence of 9 years in an adult prison. Here are some additional excerpted highlights from this interview we are encouraging audiences to listen into:

“May 18, 1997 when I was sentenced. The judge said “I am under no belief that sending you to prison would help,” but he did it anyway. I was 5’5, 125 lbs and I had stories in my head (Makes me Wanna Holler, Malcolm X, read books about incarceration before it even happened to me) I understood what incarceration was, but finding out I would be gone for nearly a decade, you walk back to your cell, drained and needing a way to deal

with it. The way I dealt with it was to be a writer.”

“Real tensions between when we allow people to be truly forgiven, and forgiven based on the fact they have full access to society versus when we just need them to perform their guilt constantly. On the other hand, when will I allow myself to be forgiven, when will I stop feeling the need to perform my guilt publicly, and I don’t have the answer to either one of those.”

We checked out Felon from the Ossining Public Library and read the work cover to cover in one sitting. There is no doubt that reading and writing helps Betts process the wounds of the prison experience, as well as reconcile the mistakes and circumstances that lead to his arrest. The content is gripping; his lyrical command is one of true talent (no wonder he has earned so many awards!). Betts makes visible, and poetic, the very real problems and hurdles we have constructed for those desiring to reform, restart, and dream a new life upon release. I was particularly drawn to the ways Betts writes ideas of freedom and oppression in poems about voting or ambition. The link between reading and writing is deeply connected for Betts. In a recent Washington Post oped he wrote, “Prison is the world’s most universal method of torture, and books are central to the fight against disappearing that follows a prison sentence." Betts’s poem “Essay on Reentry” holds all of this in its minute particulars. “No words exist for the years that we’ve lost to prison.” As I read his writing, I could see the landscapes in gray “that had become them” while also seeing time in the abstract. The cadence draws the readers into the idea of “more years than freedom.” And the cumulative effect of all Betts’s labor- poetic, legal, and cultural- can help us all, systemically, and those behind bars, “find us some free.”

Learning Links:

Felon: Poems a book by Reginald Dwayne Betts (bookshop.org)

YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pr3sJj78nT4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icQjIbX8TGg

Reginald Betts Website: https://www.dwaynebetts.com/

through poetry and personal stories.

In 2019, Betts won the National Magazine Award in the Essays and Criticism category for his NY Times Magazine essay that chronicles his journey from prison to becoming a licensed attorney, awarded a Radcliffe Fellowship from Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Emerson Fellow at New America, and most recently a Civil Society Fellow at Aspen. Betts holds a J.D. from Yale Law School. In Betts’ interview with Michal Martin, for Amanpour and Company, a PBS program and organization under PBS, he speaks about the impact of incarceration on identity, the power of written word, and the importance of forgiveness (full interview in YouTube link provided below). “I didn’t believe that my life was more valuable than the risks I was taking” said Betts as a 16 years old – sentence of 9 years in an adult prison. Here are some additional excerpted highlights from this interview we are encouraging audiences to listen into:

“May 18, 1997 when I was sentenced. The judge said “I am under no belief that sending you to prison would help,” but he did it anyway. I was 5’5, 125 lbs and I had stories in my head (Makes me Wanna Holler, Malcolm X, read books about incarceration before it even happened to me) I understood what incarceration was, but finding out I would be gone for nearly a decade, you walk back to your cell, drained and needing a way to deal

with it. The way I dealt with it was to be a writer.”

“Real tensions between when we allow people to be truly forgiven, and forgiven based on the fact they have full access to society versus when we just need them to perform their guilt constantly. On the other hand, when will I allow myself to be forgiven, when will I stop feeling the need to perform my guilt publicly, and I don’t have the answer to either one of those.”

We checked out Felon from the Ossining Public Library and read the work cover to cover in one sitting. There is no doubt that reading and writing helps Betts process the wounds of the prison experience, as well as reconcile the mistakes and circumstances that lead to his arrest. The content is gripping; his lyrical command is one of true talent (no wonder he has earned so many awards!). Betts makes visible, and poetic, the very real problems and hurdles we have constructed for those desiring to reform, restart, and dream a new life upon release. I was particularly drawn to the ways Betts writes ideas of freedom and oppression in poems about voting or ambition. The link between reading and writing is deeply connected for Betts. In a recent Washington Post oped he wrote, “Prison is the world’s most universal method of torture, and books are central to the fight against disappearing that follows a prison sentence." Betts’s poem “Essay on Reentry” holds all of this in its minute particulars. “No words exist for the years that we’ve lost to prison.” As I read his writing, I could see the landscapes in gray “that had become them” while also seeing time in the abstract. The cadence draws the readers into the idea of “more years than freedom.” And the cumulative effect of all Betts’s labor- poetic, legal, and cultural- can help us all, systemically, and those behind bars, “find us some free.”

Learning Links:

Felon: Poems a book by Reginald Dwayne Betts (bookshop.org)

YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pr3sJj78nT4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icQjIbX8TGg

Reginald Betts Website: https://www.dwaynebetts.com/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed